Introduction

Location Map

Base Map

Database Schema

Conventions

GIS Analyses

Flowchart

GIS Concepts

Results

Conclusion

References

Introduction

Logjams: Explaining Variation of In-Stream Wood Loads along the Colorado Front Range

Natalie Beckman | Geosciences, College of Natural Resources

Theresa Jedd | Political Science, College of Liberal Arts

Collecting data along Boulder Creek in Eldorado Canyon State Park. 5 October 2010.

ABSTRACT

Historical documents and recent field studies suggest that resource use within the Colorado Rockies during the past two centuries has reduced the wood loads and frequency of wood jams along most forested streams. Recent research has also shown that streams play a significant role in the sequestration and transport of organic carbon, meaning that instream wood, which tends to slow the transport of carbon and encourage its uptake in the riverine environment, may have effects which extend beyond streams and into the global carbon cycle. Our project spatially depicts the effects of past and present resource management on instream wood loads and logjam frequency along Colorado’s Front Range. We created a database that includes wood loads and jam locations for channel reaches within national park, national forest, and state park jurisdictions. We compare wood loads and jam frequency based on stream characteristics, past and present fire management, flow alteration, recreational access and logging history. Information centrally located in this GIS database was analyzed to quantify the degree of human impact. Collected field data was input and stored as GIS shapefiles-- with point locations for each jam. GIS was also used to organize existing spatial data on management jurisdiction and flow regulation. In addition, GIS was used to generate data regarding recreational access (proxied by distance from roads/trails). We hypothesized that more highly impacted reaches (as measured by easy access and high flow regulation-- both of which change with varying protection mechanisms and management protocols) will demonstrate lower wood loads, and by implication higher carbon flux and lower return of carbon and nutrients to the surrounding ecosystem. Quantified effects of human impacts on logjams can be used to influence future management decisions.

BACKGROUND

Human Impacts on the Natural Environment: Why study logjams?

Naturally recruited wood along Bennett Creek in Arapahoe-Roosevelt National Forest. Jams store sediment, “promote localized scour of the bed and banks and formation of pools, and provides over-head cover for fish and substrate diversity for aquatic insects (1)."

Photo credit: N. Beckman.

Human Impacts on Streams. Ever since the early days of Anglo-European colonization in the Colorado Rocky Mountains, humans have made major structural changes to the natural environment. During the 1870s, miners and homesteaders arrived in what is now Rocky Mountain National Park and surrounding lands. Driven by expanding ranching operations on the plains at the Eastern base of the Rockies, water diversion projects were constructed to feed the growing demand for water in both agricultural operations and sprouting municipalities along the Colorado Front Range. Water diversion projects such as the Grand Ditch, which is a canal system that began diverting water from the Colorado River basin in the late 1890s (2), have since drastically changed natural stream-flow regimes. Our project examines the role of upstream water diversion projects in downstream natural logjam formation. The findings can be used to examine general management practices and their impacts on natural jam formation. For example, what impact does decreased flow volume have on jam formation? Do diversions--which tend to reduce the magnitude of peak snow-melt runoff flows in the late spring-- make it less likely that in-stream woods loads A) are present, and B) develop into channel-spanning logjams?

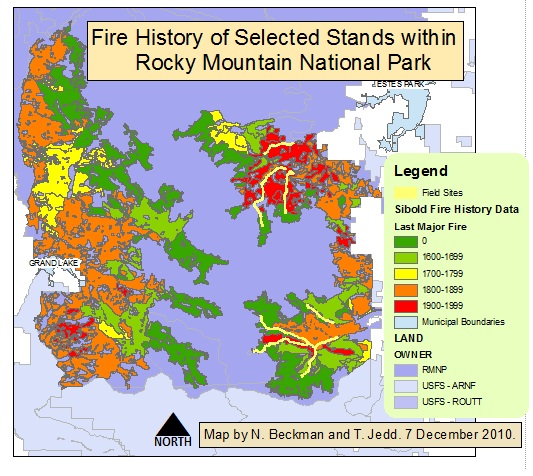

Human Impacts on Forests. We are interested in the effect of other types of human impact, too—human impacts on forests have also been ongoing since Anglo-European settlement. Logging and fire events alter the amount and characteristics of standing wood around streams. We have fire history data for forest stands within the Rocky Mountain National Park that consists of a shapefile (the basic ArcGIS spatial data layer) with date of last burn (3).

The map at right spatially depicts the fire history data we have obtained for forest stands within Rocky Mountain National Park.

Major alteration of forest and stream channel characteristics took place during the “tie drive” period. As the American railroad network expanded in the Western states, stream networks were used for transport of timber to be milled into railroad ties.

Tie drives in the Rocky Mountain Region greatly altered stream channel characteristics. Cheyenne National Forest, Wyoming (5).

Our basic research questions have to do with quantifying the effects of human impacts on stream and forest characteristics. How do upstream diversions affect in-stream wood loads and jam accumulations? How does fire history impact jams? Also, since these factors vary across land ownership type, how does land ownership type (National Park, National Forest, and State Park) affect the density of jams? Finally, at a basic level, how does recreational access affect jam density?

Our general hypothesis is that the range of human impacts we've outlined-- whether they be to alter the region's fire regime or to regulate stream flows-- will effectively reduce the number and size of log jams in the Front Range.

N. Beckman collected data on a number of reaches within the Colorado Front Range area and we also use data collected during the 2010 field season by E. Wohl. One reach is within CO State Park jurisdiction (Eldorado Canyon) for which both N. Beckman and T. Jedd gathered data.

------------------------------

Citations

1. Photo Credit: Natalie Beckman. July 8 2010. Caption: E. Wohl, 2010. http://warnercnr.colostate.edu/geo/front_range/LandUse.php

2. http://www.nps.gov/romo/historyculture/time_line_of_historic_events.htm3. GIS data (based on work by J. Sibold, Colorado State University) provided from Rocky Mountain National Park’s GIS unit:

Ron Thomas, GIS Specialist, Vegetation Mapping Coordinator

Rocky Mountain National Park, Estes Park, CO. 80517, (970) 586-1292

4. Photo credit: Patrick Cullis. http://www.mytowncolorado.com/

5. Photo credit: American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming. Reposted on: http://warnercnr.colostate.edu/geo/front_range/LandUse.php

--

Created 29 November 2010. Last modified 7 December 2010. TMJ